1949

In May 1949, the artist returns to Diessen. In July he is one of the founding members of the Gruppe der Gegenstandslosen (Group of Non-Objective Artists) formed on the initiative of the art critic John Anthony Thwaites at the Munich gallery run by Etta and Otto Stangl. Later that year, the group changes its name to ZEN 49. Its other members are Rupprecht Geiger, Willi Baumeister, Rolf Cavael, Gerhard Fietz, Willy Hempel, the sculptor Brigitte Matschinsky-Denninghoff and the art historians Ludwig Grote and Franz Roh. Like the artists of Der Blaue Reiter group before them, they endeavour to work together to help abstract art gain acceptance and recognition and to contribute to a moral fresh start in Germany. The group continues to exhibit until 1957, inviting the participation of numerous other artists.

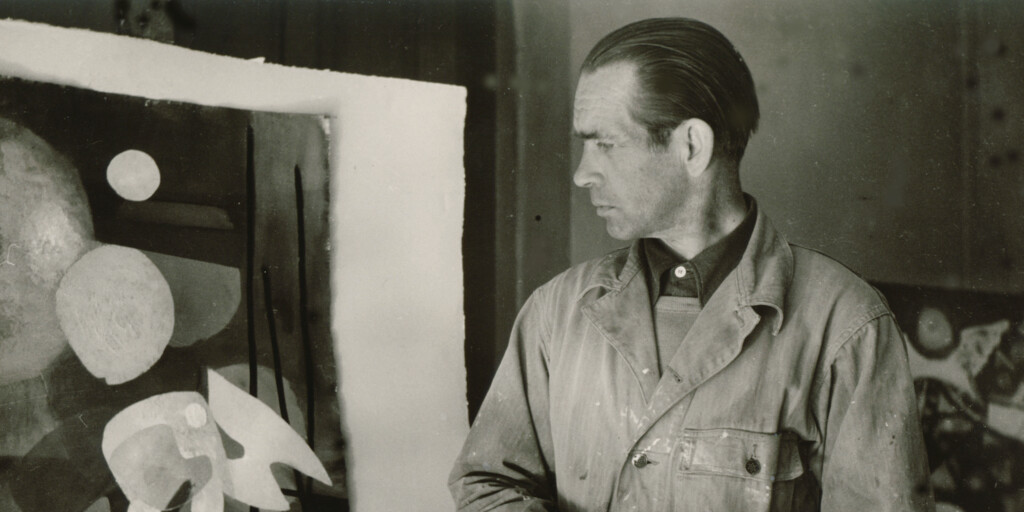

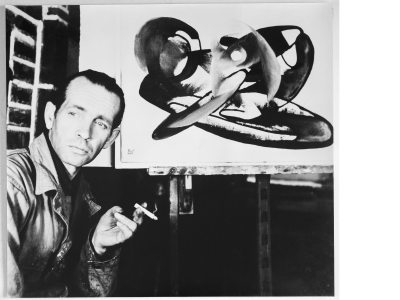

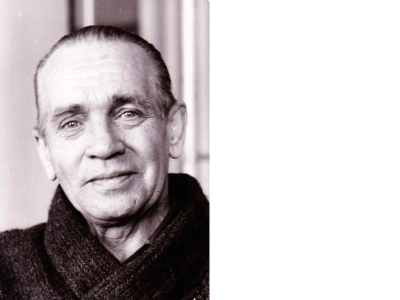

Fritz Winter, c. 1949, © Fritz-Winter-Haus, Ahlen

1950

The first exhibition of the ZEN 49 artists’ group is held at the Munich Central Collecting Point. Winter travels to Italy and France. In Paris he becomes acquainted with Hans Hartung and Pierre Soulages and, through them, with French Art Informel. With the art historian Werner Haftmann he travels to the Venice Biennale, where he receives an award. Over the following years, Haftmann will be one of the most influential champions and interpreters of Winter’s art. Thanks to the Galerie Marbach in Bern, which agrees to purchase a set number of works every month, Winter enjoys a modicum of financial security for the first time. An exhibition put together by the Moderne Galerie Stangl travels to Witten, Wuppertal, Essen, Hagen, Stuttgart and Basel. The artist’s principal gallerists now are Stangl as well as Günther Franke in Munich, Ferdinand Möller (now in Cologne) and Walter Schüler in Berlin. In the years to come he will also be represented by galleries in Paris and New York.

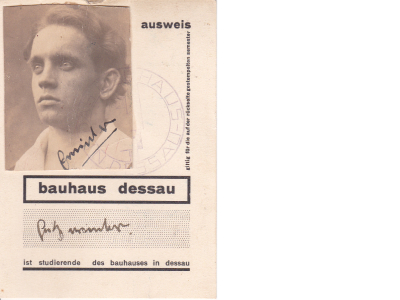

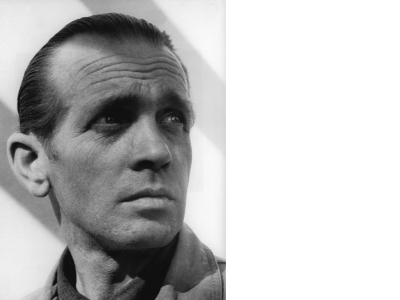

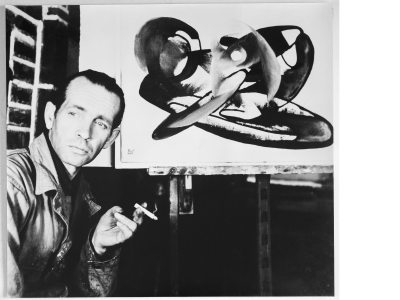

Fritz Winter, c. 1950, photo: Fritz-Winter-Haus, Ahlen

1951/52

Margarete and Fritz Winter get married. Winter joins the Deutscher Künstlerbund (Association of German Artists) in 1951. He is awarded the Domnick Prize in Stuttgart and the first prize of the Deutscher Künstlerbund in Berlin. In the following years his work is shown in a rapid succession of solo and group exhibitions, among them a presentation at the Kunsthalle Bremen in 1952.

1953

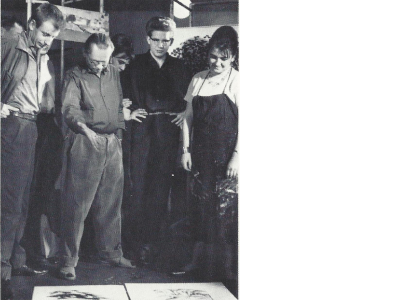

As part of the project “Abstract Painters Teach”, initiated by Gustav Hassenpflug, he takes on a three-month position as a visiting lecturer at the Landeskunstschule Hamburg. His final lecture, on “Compositional Elements in Painting”, is published in 1959.

1954

Together with Willi Baumeister and Ernst Wilhelm Nay, Winter resigns from the Deutscher Künstlerbund in protest. The artists accuse Karl Hofer, the Künstlerbund’s first chairman, of making disparaging remarks about the importance of abstract painting.

1955

On 1 May, Winter takes up a professorship at the Werkakademie (later Staatliche Hochschule für bildende Künste) in Kassel, where he becomes a colleague of Arnold Bode, the founding father of the documenta. At the first documenta, which opens in the city in July, Winter shows seven paintings, among them the monumental Composition in Front of Blue and Yellow, which is prominently displayed in the gallery devoted to painting. In the years to come, Winter will take on increasing responsibility for the organisation of the documenta. Winter commutes between Diessen and Kassel, where he will teach until 1970.

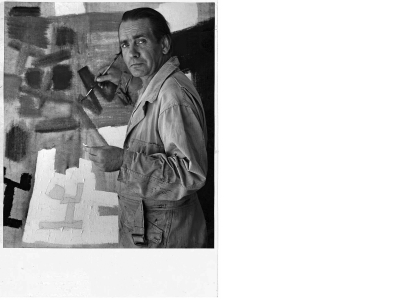

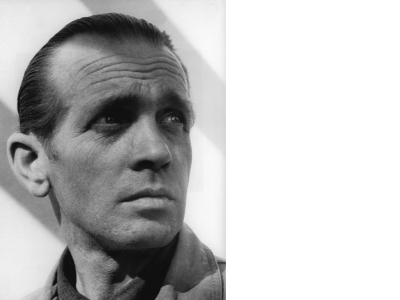

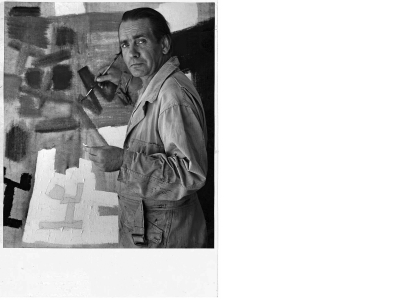

Fritz Winter, um 1955, Foto: Fritz-Winter-Haus, Ahlen

1956/57

In 1956 he is awarded the Cornelius Prize of the City of Düsseldorf. An exhibition devoted to ZEN 49 tours college towns on the East Coast of the USA. In 1957, Winter designs a large-format mosaic for one of the exits of the Hansaplatz underground station as part of the Interbau – the International Building Exhibition in Berlin. In the same year, Werner Haftmann’s book Fritz Winter: Triebkräfte der Erde is published by Piper Verlag. By 1960, some 70,000 copies of the publication are in circulation.

1958

In October, Winter’s long-time companion and wife Margarete dies. Her support had been crucial to his success. The artist is at the height of his career, with three solo shows and 15 group exhibitions worldwide that year.